1 State of the Art

Abba Naor was born in 1928 in Kovno as Abba Nauchowicz; he grew up there with his father Hirsch, who was a photographer, his mother Chana, who worked at home, and with his two brothers. The Holocaust destroyed this family and in 1947 Abba, who now called himself Naor, went to Palestine and became a solider. Later he worked for the Israeli secret service (Raim, 2008, p. 97). Since the 1980s, he regularly visits school classes in Germany to tell his story (Hammermann, 2013, p. 310). As a Jewish survivor of the Holocaust he holds the Israeli and the German citizenship: half of the year, he lives in Munich and is involved in the educational work of the memorial site of Dachau; he also holds the position of the Vice President of the Dachau Committee, the representation of the former prisoners of Dachau; half of the year, he lives in Rehovot near Tel Aviv spending time with his family. In the best sense of the word, he is a wanderer between worlds (Sabrow, 2012, p. 25).

For three years, I have accompanied him on his visits to school classes in Bavaria. I am interested in the structure of his testimony as well as in his interaction with the students. In these past years, Abba Naor and I have gotten to know each other better. Our relationship is characterized by scientific interest and personal trust.

When I first started to work on the topic, I found a void: There are hardly any empirical studies that deal with the impact of contemporary witnesses giving their testimonies to school classes. It is stressed that an encounter with the person who was “there” brings the Holocaust closer to young people (Kaiser, 2018, p. 76). Most of the German studies are carried out by historians and reflect the source value of the testimonies and students’ reactions to them (Bertram, 2017, p. 37).

In their qualitative micro-study, Obens and Geißler-Jagodzinski (2009) focus on both: By doing participating observations of the sessions with survivors in school classes and by interviewing the students, they could show that students tend to mix the story of the victims with their own family history, which quite often are the stories of the perpetrators. Moreover, the aura of the contemporary witnesses keeps young people from noticing contradictions in the narrations they hear. Demmer (2015) also works qualitatively; she examines how the knowledge conveyed by contemporary witnesses can be contextualized with other knowledge resources.

The quantitative study “Geschichtsbewusstein, historisches Wissen und Interesse” [Awareness of history, historical knowledge and interest] by Galda (2013) is significant: She interviewed 779 secondary school students. Regarding conversations with contemporary witnesses, she identified four types of students dealing with the testimonies: the “Oberflächlichen” (the superficials), the “emotional Angesprochenen” (the emotional audience), the “historisch Interessierten” (historically interested people), the “Anfänger” (the beginners) (Galda, 2013, p. 234). Feldmann-Wojtachnia and Hofmann’s (2006) quantitative study of 1.000 students points in a similar direction and focus on emotional learning processes.

To this day, contemporary witnesses and their actions are subject to a certain scepticism, especially in the school subject of history (Meseth, 2008):

“Zeitzeugen, die Gewalt und Verfolgung erfahren haben, eignen sich daher eher nicht für die Befragung im Geschichtsunterricht, jedenfalls nicht, wenn historisches Denken (z.B. die Vermittlung geschichtstheoretischer Grundlagen oder die Notwendigkeit von Quellenkritik) gefördert werden soll.” (Bertram, 2017, pp. 43–44)

[“Contemporary witnesses who have experienced violence and persecution are therefore not suitable for questioning in history lessons, at least not if historical thinking (e.g. the teaching of historical theoretical foundations or the necessity of source criticism) is to be promoted.”]

This is an important starting point for me: When I take part in those sessions with Abba Naor, on the one hand I also feel emotionally overwhelmed in the classroom at certain points. On the other hand, I see a 90 year old man and students in interaction; an interest in his story and in the question “how could this happen” becomes obvious, too.

2 Data Base and Study Design

The case study is a qualitative one and aims at a detailed description of “what’s going on in the classroom”. The considerations are based on the following data:

a participating observation during the training of guides at the Dachau Concentration Camp Memorial Site (November 2016),

four participating observations with a focus on interaction at secondary schools (2017 to 2018, done by myself),

four participating observations with a focus on interaction at secondary schools (2018, done by a research student, a volunteer at the memorial site of Dachau, who accompanied Abba Naor to the schools),

a transcription of a witness session with Abba Naor and a school class in the Max Mannheimer Study Centre.

Furthermore, I used his book Ich sang für die SS. Mein Weg vom Ghetto zum israelischen Geheimdienst [I sang for the SS. My Way from the Ghetto to the Israeli Secret Service] (2018) and I refer to an interview he gave to the USHMM in 1999 (https://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/irn87617) and an interview I conducted in Munich (February 2019). The different materials are analysed with the help of my qualitative empirical and language education background; thus connections between the data sources help to gradually develop a description. My study is also influenced by Horsky (1988): In the 1980s she accompanied Holocaust survivors to school classes and condensed her observations in a narration. Of course, I am aware that the many conversations and encounters with Abba Naor have shaped my perspective (Ellis & Rawicki, 2014; Kröger, 2010).

The quotes of Abba Noar in this paper are mainly based on the transcription of his talk in the Max Mannheimer Study Centre but were cross-checked and compared with the information from the participating observations. German quotations were translated into English and both versions are reproduced. English statements by Abba Naor were not translated into German.

3 Framing of a Living Testimony

3.1 Abba Naor’s Self-Positioning

Recently, Shenker pointed out how important it is to bear in mind that institutions mediate forms of witnessing: “That is not to suggest that testimonies of living survivors delivered in person at museums, archives, and other spaces are raw accounts in contrast to their framed audio-visual versions.” (Shenker, 2015, p. X) Therefore, the framing of Abba Naor’s testimony and the impact of the institutional setting in Bavarian schools is considered.

In the Oral History Interview Abba Naor gave to the USHMM in 1999, he was asked by the interviewer if he had told his story to his children. Abba Naor answered: “No, not exactly.” More important for him was his granddaughter who came home from school one day and said:

“‘Look, we got to write our roots. Who are you?’ […] She just asked me questions and I answered. ‘Who the family was? How big the family was.’ And so on. And I told her the story in a, in a funny way because I was afraid maybe she will be touched too much. I was always very careful with my children and my grandchildren. I got five of them. I didn’t want to them to be to be […] troubled with this, and I didn’t want them to feel sorry for me. And I think I am not the only one of survivors who is trying to play the hard guy, you know. Tough guy, ya.” (Tape 2, 21:38–23:12, https://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/irn87617)

When he talks about the beginning of his activity as a contemporary witness Abba Naor uses a similar structure of argumentation. Again, the impetus is set from outside, by his grandson. At that time – at the end of the 1980s – Abba Naor lived in Hannover. He could not resist when his youngest grandson asked him to tell the story at school. Until then, he had refused to talk about his story in public. Since the session was quite successful, he offered the Ministry of Education of the German State of Niedersachsen to visit schools. In 1992, he was invited to come to the International Youth Meeting in Dachau (Naor & Zeller, 2014, pp. 249–250).

In an interview I conducted in February 2019, he stresses the role his family played in helping him to cope with his past. He also emphasises the importance of sharing his story:

“Und gerade zu bekommen eine Möglichkeiten, bisschen rauszureden. Auch dieser Gang zu die Schulen. Das gibt eine Möglichkeit, wenigstens ein paar Stunden, die Geschichte zu erzählen, mit jemanden, zusammen, ihn reinführen in mein Leben, das macht es leichter.”

[“And just to get a chance to talk a little out of it. Also going to the schools. That gives a possibility, at least a few hours, to tell the story, with someone, together, to lead him into my life, that makes it easier.”] (Oral History Interview with Abba Naor, 01.02.2019, 38:56–39:15)

Furthermore, he is aware that he is organizing his memories in a specific way; he reflects the context of his talks and the boundaries the context sets. Stories, therefore, are necessarily partial and incomplete (Sheftel, 2018, p. 292). In addition, as Abba Naor points out they are shaped by the audience that is awaiting him:

“Und schon, wenn ich ins Bett gehe, fängt schon der Kop an zu arbeiten. Wo bin ich morgen? Wen hab ich vor mir? Und was werde ich denen erzählen? Was kann er mir leisten zu erzählen? Wieviel kann ich diese Kinder irgendwie reinnehmen in diesen mein Leben? Wieviel kann ich die belasten? Und wie viel soll ich die nicht belasten? Weil Kinder sind mir wichtig. […] Jedes Kind ist mir wichtig. Das sind doch Kinder. Sind doch keine Erwachsene.”

“And already, when I go to bed, the mind starts working. Where will I be tomorrow? Whom will I have in front of me? And what will I tell them? How much can I somehow take these children into my life? How much can I burden them? And how much should I not burden them? Because children are important to me. [...] Every child is important to me. They are children. They're not adults.” (Oral History Interview with Abba Naor, 01.02.2019, 39:33–40:16)

3.2 Institutional Context

When Abba Noar comes to Munich, he is invited by the Stiftung Bayerische Gedenkstätten [Foundation of Bavarian Memorial Sites], which oversees the sites Dachau and Flossenbürg. Since 2007, Abba Naor has been reporting about his fate during National Socialism in Bavarian schools. The Dachau Memorial site organizes his visits to schools. A volunteer accompanies him and helps set up his presentation. On average, Abba Naor visits three to four schools per week, beginning at 10 a.m., leaving at around 12 p.m. Sessions take place at the concentration camp memorial and at the Max Mannheimer Study Centre in Dachau as well.

Generally, he has a contact person at the school who welcomes him. Abba Naor likes to speak in front of many students, usually there are 50 to 100. The students are aged between 14 und 18 years. The eyewitness session usually takes two lessons and a break: After an introduction by the headmaster or a teacher, the survivor talks for up to 80 minutes; during that time he mostly speaks monologically; from time to time he interacts with the students and asks them questions. On average, 10 to 20 minutes are left for the students to ask their questions. A teacher moderates the session, sometimes also the headmaster.

Abba Naor stands in front of the students, who are sittings in rows, using a PPP with pictures and maps. The pictures serve mainly to support and illustrate his narration. If he is well he refuses to use a microphone. His only props are a water bottle and his book. These media serve as artefacts, which the survivor also explicitly integrates into a mediation setting (Demmer, 2015, p. 70).

After the conversation, Abba Naor leaves the school. He wants to be on his own and drives back to Munich.

4 The Structure of the Living Testimony

4.1 The Monologue

During the sessions with Abba Noar and the students, a special atmosphere is created as opposed to regular school teaching. When analysing the protocols his desire to balance the students’ feelings becomes obvious. All sessions are based on a similar structure; the structure offers a connection to the so-called “wave dramaturgy” [“Wellendramaturgie”] used in broadcast series. In contrast to a classical drama with a climax in the third act, which separates the rising and falling plot from each other, pieces with a wave dramaturgy follow a different logic: The narration consists of several arcs of tension that follow each other; listeners can relax emotionally after an exciting episode, before the action rises again (Rogge & Rogge, 2004).

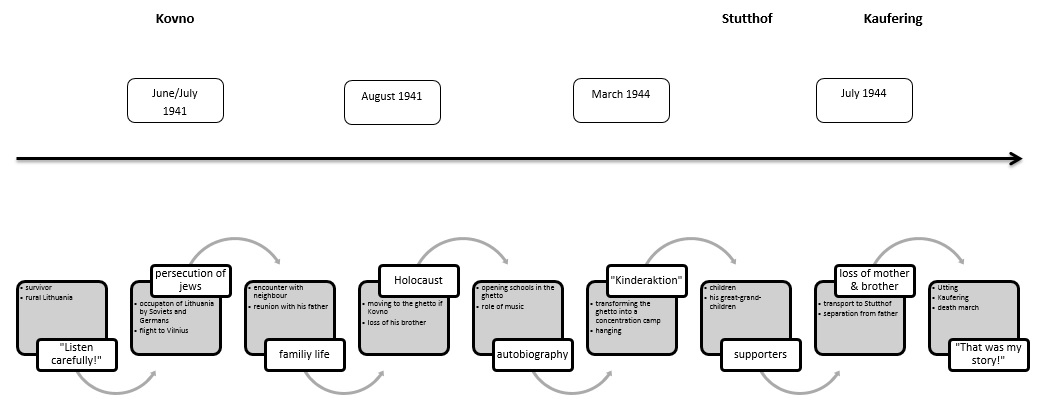

Abba Naor divides his testimony with the help of wave dramaturgy: Every 20 minutes there is a narrative climax that affects either his life or history in general. At the beginning he needs 20 minutes before he reaches a first climax; after the last climax another 15 minutes are required to end (Figure 1).

To begin with, he starts reflecting his role as a survivor and eyewitness. The students are asked to listen (“Hört gut zu!” [“Listen carefully!”]), there are not many of them left. He stresses that he gives his testimony for all the people who cannot bear witness any longer. Then he talks about Lithuania, the place where he was born. He describes the country of his childhood as a beautiful, agricultural environment where people of different religions and nations lived together peacefully. Although he states that Antisemitism already existed at that time, he is convinced: “Ein bisschen Antisemitismus ‒ damit konnte man leben.” [“With a little antisemitism, you could live.”] (Participating Observation, March 2018). He explains in greater detail:

“Das war unsere Heimat. Juden kamen nach Litauen vor (ungefähr) 600 Jahren ungefähr. Streng katholisches Land. Antisemitismus war immer vorhanden. Aber man konnte damit leben. Man gewöhnte sich daran, mal (manchmal) so beschimpft zu werden, auch heute ist es manchmal so, in manchen Ländern. In jedem Land, kein Problem.”

[“This was our home. Jews came to Lithuania about 600 years ago. Strictly Catholic country. Antisemitism was always present. However, one could live with it. One got used to being insulted (sometimes) like that; even today, it is sometimes like that, in some countries. In every country, no problem.”] (Transcription Video, 50–63).

The situation changed when the Soviets occupied Lithuania (June 1940): Abba was thrilled by the young pioneers and wanted to become a member. When the Germans invaded Lithuania in June 1941 the atmosphere was full of tension; so his family decided to flee to Vilnius. Nevertheless, this was not a safe place for Jews either; so, the family set out again. His parents split up; his father returned to Kovno alone; his mother started the way back with the three children – Chaim (born 1926), Abba (born 1928) und Berale (born 1938). The reason for wandering between the two Lithuanian cities was that his parents already knew how Jews were being persecuted in Poland. Talking to the classes Abba Naor reaches a first climax when he shows a picture of devastated synagogues and killed Jews. After this brutal picture, the tension is gradually released: He tells the students, that he had to find his father when they were back in Kovno. He, aged 13, was sent to their former home where a neighbour shouted out: “The Jews are already back!” Finally, the family was reunited and they were quite happy that some aunts and uncles had survived. Abba Naor goes on, telling about a happy family life, with his mother, his two brothers and his father. He repeatedly stresses that they were a “normal family”.

The action resumes tension and a second wave arc is built up: In July 1941, a command was issued by the Nazi-German occupying forces. All Jews had to move to Slobodka by the 15th of August 1941. Two ghettos, a small one and a larger one were being set up. The family had to go there and people were “not too unhappy”, as he recalls. They felt safer since they were all by themselves. The Nauchowicz family moved to the ghetto, together with 23 other family members. As they had no idea of what life in the ghetto was like, children were sent to get food. Among them was Abba’s older brother Chaim. The Gestapo caught him. All of the 26 children who were trying to illegally obtain food were murdered that day in the IX. Fort near Kovno, by the SS. It was in these forts that his brother and the other children were shot. But not only them. Many Jews from all over Europe were killed at that place – before the conference of Wannsee (1942). Abba Naor continues his narration by referring to the beginning of the Holocaust that started in Lithuania. He mentions, though not always by name, the man who was responsible for the “Jewish action” in Lithuania: Karl Jäger (1888–1959), often he shows a picture of him. This is the second climax of his story. After these atrocities, he speaks about positive things: Schools were opened in the ghetto and concerts were given: For example, the ghetto administration permitted a concert, which took place in the local Yeshiva – after that concert Abba sang with the orchestra, for which he got extra food. At that point the survivor refers to his book “I sang for the SS”, which he wrote and which – according to him – the students should read. In this book photos of himself as a young man are published which he likes to show: “Wo sind die Mädchen? Schaut, so habe ich ausgesehen mit 17. War ich hübscher Junge?” [“Where are the girls? Look, this is what I looked like when I was 17. Wasn’t I a cute guy?”] (Transcription Video, 425–426).

His story is now moving towards the third arc of tension: Kovno ghetto was transformed into a concentration camp in September 1943. Public executions were common and fear was a constant companion. The family was particularly worried about Berale. His family managed to hide his little brother from the Nazis during the so-called “Kinderaktion” where around 1.000 children were murdered (March 1944). Thus, he reaches another turning point in his story and talks about children during the war, also about his grandchildren. Again he illustrates his message with a picture: “Aber warum zeig ich dieses Bild? Die sind ja lebendige Kinder, meine Urenkel. Aber ist ja ein Grund da, warum ich diese Bild zeige.” [“But why do I show this picture? They are living children, my great-grandchildren. However, there is a reason why I show this picture."] (Transcription Video, 498–499). The questions and explanations lead to an appeal not to forget the helpers. He mentions Anton Schmid (1900–1942, soldier of the German Wehrmacht), who saved Jews in Lithuania. He paid for his courageous actions with his life.

Tension is built up by reporting on further historical events: In July 1944, his family was loaded onto ships on which the family members were taken across the Memel to Gdansk. After a couple of days, they arrived at the concentration camp Stutthof near Gdansk; his father and Abba were separated from his mother and younger brother, as they had to stay in different parts of the concentration camp. During a selection, a guard realized that Hirsch was Abba’s father, so Hirsch was deported to Allach, a sub camp of the Dachau concentration camp. At the 26th of July Abba’s mother and his younger brother were deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau and murdered the same day. This farewell is still painful for him today – another sad climax of his life. He quickly tells the story of his pursuit, within 10 to 15 minutes. After the loss of his family, these events seem almost adventurous and relieving: He arrived at Utting, where he and other prisoners had to build the barracks (August 1944); here he had different jobs and friends who held together. Abba Naor “volunteered” to work at another sub camp of the Dachau concentration camp: Kaufering I where the “living conditions” were even worse than in Utting. The reason for “volunteering” was that he hoped to find his father. From Kaufering they were sent on a death march and liberated on the 2nd of May 1945 near Waakirchen by US soldiers. Abba Naor ends his narration with the words: “Und das war meine Erzählung. Wenn ihr Fragen habt, würde ich sie gerne beantworten.” [“And that was my story. If you have any questions, I would like to answer them.”] (Transcription Video, 821–822).

To sum it up, in his sessions with school classes, Abba Naor mentions perpetrators, bystanders and helpers. In the case of victims, he alternates between naming numbers and describing the faith of his own family. The dramaturgy of wave helps him to communicate about antisemitism in Lithuania. Within his story, the children who were killed are of special concern for him. Significantly, he also addresses the students as children. Before doing so, he asks for their consent “Darf ich Kinder sagen?” [“I am allowed to say children?”] (Participating Observation, February 2017).

4.2 The Dialogical Structure

The personal account of the contemporary witness is a special form of communication. Therefore, the framing as well as the interaction between contemporary witness and students have an influence on the story being told (Schreiber, 2009). Even though he mainly gives a lecture, there are also dialogical phases. The dialogues are initiated by questions. It is not always immediately obvious to the listener whether the contemporary witness expects an answer to his questions or not. He uses various forms of questioning that require different reactions of the audience.

Firstly, Abba Naor uses rhetorical questions to which he does not expect an answer. Rather, he tries to attract the listeners’ attention, especially for topics which are important to him and which are thus highlighted. For example, he talks about the concentration camp and the problems children had there: “Was macht man mit Kinder im KZ?” [“What do you do with children in concentration camps?”] (Participating Observation, 26.02.2018).

Secondly, he asks questions to structure his monologue, especially the arcs of tension. Questions help him to make the transition, to build-up, and to reduce tension. With the help of the questions, he can talk about the atrocities that are looming: After talking about his happy family life, he points out: “Wo sind die Mädchen? War ich nicht ein schöner Junge?” [“Where are the girls? Haven’t I been a cute guy?”] (Transcription Video, 425–426).

Finally, his remarks contain questions to which he expects an answer from the audience. This is not always understandable for the audience, especially when thinkings of the rhetorical and structuring questions. The context in which he asks these questions refers to the beginning and end of his narration. The content of these questions is fixed on the persecution of the Jews and requires a specific response of the listeners. On the one hand, Jews are portrayed as scapegoats, as in his remarks on the first climax: “Und die [lithauische Regierung] haben angefangen Ordnung zu machen. Vor allem suchten sie die Schuldigen. […] Und diese Schuldigen sind gefunden worden? Wer konnte es gewesen sein?” [“And they [Lithuanian government] began to make order. Above all, they sought the culprits. [...] And these culprits were found? Who were the culprits?”] (Transcription Video, 162–166). Abba Naor expects the students to take on the role of perpetrators. The culprits are – from the perspective of the time – the Jews. During the participating observations, one feels an atmosphere of uneasiness among the students to answer this question. However, the survivor insists until he hears the answer he expects – the Jews – from the students.

He also calls on the students to provide evidence: they see pictures of children of Jewish faith who were murdered. He then shows photos of his great-grandchildren. These images are combined with the following questions: “But why do I show this image? They are living children, my great-grandchildren. But that's one reason why I show this picture?” (Transcription Video, 498–499) Again, he waits for the answer that satisfies him. Only then does he continue with his story. Until then he calls upon various students, who in turn often have to approach the answer. Abba Naor continues with his story when he hears statements like: “Die sehen aus wie alle anderen.” [“They look like everybody else.”] (Transcription Video, 507). The students have to articulate the finding that children of Jewish faith do not look any different from other children.

At the end of his testimony, talking about Utting, he unfolds a “pig scene” (Naor & Zeller, 2018, pp. 151–152; Ganor, 2009, pp. 180–181). When they accompanied their guard to the Bavarian village and had to wait for him, they saw pigs in front of their trough, eating and grunting. Abba Naor draws a comparison: “Denkt doch nach: Was war das Gemeinsame, zwischen uns und den Schweinen, ha?” [“Think: what did we have in common with the pigs?”] (Transcription Video, 691–692). Here, too, the students have difficulties; they are expected to answer that the Jews were sentenced to death. No sooner does Abba Naor hear this answer than he asks the next question: “Das war das Gemeinsame, wir waren alle beide zu Tode verurteilt, nur das Schwein hatte es viel schöner als wir. Und was war das Schönere?” [“We were both sentenced to death, only the pig had it much nicer than we did. And what was the more beautiful thing?”] (Transcription Video, 702–704). Here, he expects the students to point out the food and inhuman treatment of the prisoners.

Additionally, he gives the students tasks; they have to estimate how many percent of Jewish Lithuanian children survived the Holocaust: “Und wenn der Krieg vorbei war, sind von diesen 250.000, 4% am Leben geblieben. Ich nehme an ihr könnt gut rechnen? Wer von euch kann denn gut rechnen? Junger Mann wie viel ist vier Prozent von 250.000?” [“And when the war was over, 4% of these 250.000 Jewish children are still alive. Which of you can calculate well? Young man, what is four percent of 250.000?”] (Transcription Video, 29–31).

After he finishes his story, up to 15 minutes are left for the question-and-answer-session. The roles change, and students become active. They are interested in everyday life in the camps (“Were you hungry?”, “Did you have leisure time in the camps?”, “Were you sick in the camps?”). An important topic is liberation (“Were his/your friends liberated, too?”, “What was the feeling, being free/How did it feel to be free?”, “When did you meet your father?”). The students also want to know how he managed his life after liberation (“Where do you live?”, “Did you go back to Lithuania?”).

Only rarely do students ask questions about his native Lithuania and about antisemitic experiences. A student wants to know: “Wie ist es in Litauen? Wo Sie wieder da waren?” [“What's it like in Lithuania? When you went back?”]. The survivor explains in relative detail:

“Das Land als solches hat sich nicht verändert, die Bäume sind, die Flüsse sind da, die Menschen sind da, Antisemitismus ist auch da. Der war schon immer in Litauen da und auch heute. Die Leute haben noch nicht gelernt. Sie wollen nicht zugeben, dass die waren die ersten, die uns ermordet haben, die müssen noch dazulernen. Dabei lebten wir mit ihnen seit Generationen.”

[“The country as such has not changed, the trees are there, the rivers are there, the people are there, antisemitism is also there. It has always been there in Lithuania and still is today. The people have not yet learned. They do not want to admit that they were the first to murder us, they still have to learn. Although we had lived with them for generations.”] (Transcription Video, 914–918).

5 Concluding Remarks

This answer forms the core of his narration: Abba Naor describes Lithuania as the land of his childhood, rural in character, combined with beautiful memories. Antisemitism was and is there – then and today. His story is devoted mainly to the depiction of antisemitism in the Baltic state; to some extent he follows Snyder’s “bloodlands”: in the middle of Europe 14 million humans were killed during the National Socialist and Soviet regime (Snyder, 2015, p. 9). The audience usually expects something different; the students especially want to hear more explicitly the story of his life in the sub camps of Dachau. The Baltic country is far away from their imagination.

When describing the persecution Abba Naor constructs and deconstructs the group of the Jews. On the one hand, he addresses them collectively as “the Jews” and tells the story of how they were tortured, deported and killed. On the other hand, he stresses “normality”: His family was a “normal” one – with father, mother and brothers; they wanted to have a good life.

In a similar way, he uses questions that comprise the following perspectives: Students must put themselves in the position of the perpetrators: They have to formulate that “the Jews are to blame”. Rosenthal (1997) has proclaimed for the 3rd generation of perpetrators and bystanders that they are unable to pronounce the word “Jew” or “Jewess”. The study by Obens and Geißler-Jagodzinski (2009) show similar results: In the group discussions with students lasting longer than 140 minutes, the word “Jews” appears only ten times, although the contemporary witness in the conversations with the young people very clearly refer to their identity as Jews in Israel and their persecution as Jews in Europe. Instead, the young people speak of a “different perspective”.

Abba Naor forces the students to pronounce the word “Jew”. From an educational point of view, it has to be addressed to what extent, he overwhelms the students (Buchstein, Frech & Pohl, 2016). However, he also offers the students another perspective: According to the ideas of a Socratic dialogue, he leads the students to the insight that “the Jews” are not a race and cannot be recognized by external characteristics. Here he continues the argumentation of the “ordinary people” and pleads for normality.

In school classes quite often, the framing of the testimony of a survivor is not systematically explored. To understand the story, to appreciate the talk and to interpret critically and empathetically the survivor’s living testimony it is useful to reveal his self-positioning as well as the institutional context. This should be done, for example, by asking which memories the contemporary witness brings together in his narration, which main and secondary stories he tells (Schreiber, 2009), and which stories he is hiding.

For the discussions with Abba Naor in school classes, it would be important to shed light on the role of antisemitism in Lithuania and the resulting conclusions he draws for today.

References

DataGanor, S. (2009). Das andere Leben. Kindheit im Holocaust (5. Aufl.). Frankfurt a. M.: Fischer.

Naor, A. (2011). Der Überlebende und Zeitzeuge Abba Naor anlässlich der Feierstunde zur Umbenennung des Jugendgästehauses Dachaus in das Max-Mannheimer-Studienzentrum am 29. Juli 2010. In I. Macek, Ilse & H. Schmidt (eds.), Max Mannheimer. Überlebender, Künstler, Lebenskünstler. Ausgewählte Reden und Schriften von und über Max Mannheimer (p. 66). München: Volk Verlag.

Naor, A. & Zeller, H. (2018). Ich sang für die SS. Mein Weg vom Ghetto zum israelischen Geheimdienst (2. durchgesehene Aufl.). München: C.H. Beck.

Oral History Interview with Abba Naor. Accession Number: 1999.A.0122.1746 | RG Number: RG-50.477.1746. https://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/irn87617 [last access: 10.02.2019].

Oral History Interview with Abba Naor, 01.02.2019, Munich, Anja Ballis / Franziska Müller.

Participating Observations by Anja Ballis, November 2016, February 2017 & 2018, March 2018.

Participating Observations by a research student, May & July 2018.

Transcription of a video with Abba Naor, edited 05.10.2015, Dachau, Max Mannheimer Study Centre, www.youtube.com/watch?v=FTdTPPuXX_k&t=204s [last access: 10.02.2019].

Research Literature

Bertram, C. (2017). Zeitzeugen im Geschichtsunterricht. Chance oder Risiko für historisches Lernen? Eine randomisierte Interventionsstudie. Schwalbach/T.: Wochenschau.

Buchstein, H., Frech, S. & Pohl, K. (2016). Beutelsbacher Konsens und politische Kultur. Schwalbach/T.: Wochenschau.

Demmer, J. (2015). Artefakte und Wissensformen in biografischen Selbstpräsentationen von Zeitzeug_innen. ZISU, 4, 66–79.

Ellis, C. & Rawicki, J. (2013). Collaborative Witnessing of Survival During the Holocaust: An Exemplar of Relational Autoethnography. Qualitative Inquiry, 19(5), 366–380. DOI: 10.1177/1077800413479562.

Feldmann-Wojtachnia, E. & Hofmann, O. (2006). Erinnern, begegnen, Zukunft gestalten. Evaluation des Förderprogramms „Begegnungen mit Zeitzeugen – Lebenswege ehemaliger Zwangsarbeiter“. München: CAP.

Galda, M. (2013). Geschichtsbewusstsein, historisches Wissen und Interesse. Darstellung von Zusammenhängen und Repräsentationen in semantischen Netzwerken. Frankfurt a.M. URL: https://d-nb.info/1042934746/34 [last access: 16.02.2019].

Gedenkstätten. URL: www.stiftung-bayerische-gedenkstaetten.de/de/front-page [last access: 17.02.2019].

Hammermann, G. (2013). Zeitzeugeninterviews und Zeitzeugengespräche in der KZ-Gedenkstätte Dachau. Veranstaltungen – Bestände – Perspektiven. In R. Boehling, S. Urban & R. Bienert (eds.), Freilegungen. Überlebende – Erinnerungen – Transformationen (309–316). Göttingen: Wallstein.

Horsky, M. (1988). Man muß darüber reden. Schüler fragen KZ-Häftlinge. Wien: Elephant-Verlag.

Kaiser, W. (2018). Memories of survivors in Holocaust Education. In A. Pearce (ed.), Remembering the Holocaust in the Educational Setting (76–91). London: Routledge.

Kößler, G. (2007). Gespaltenes Lauschen. Lehrkräfte und Zeitzeugen in Schulklassen. In Fritz Bauer Institut (ed.), Zeugenschaft des Holocaust. Zwischen Trauma, Tradierung und Ermittlung (176–191). Frankfurt a.M.: Campus.

Kröger, M. (2000). Dispositionen des Zuhörens. Reflexionen zum Umgang mit Zeitzeuginnen und Zeitzeugen. In I. Hansen-Schaberg & B. Schmeichel-Falkenberg (eds.), Frauen erinnern. Widerstand ‒ Verfolgung ‒ Exil. 1933-1945 (74–98). Berlin: Weidler.

Meseth, W. (2008). Holocaust-Erziehung und Zeitzeugen. URL: https://www.bpb.de/geschichte/zeitgeschichte/geschichte-und-erinnerung/39849/bedeutung-von-zeitzeugen?p=all [last access: 16.02.2019].

Obens, K. & Geißler-Jagodzinski, C. (2009). Historisches Lernen im Zeitzeugengespräch. In Gedenkstättenrundbrief 151,10, 11–25. URL: www.gedenkstaettenforum.de/nc/gedenkstaetten-rundbrief/rundbrief/news/historisches_lernen_im_zeitzeugengespraech/ [last access: 19.02.2019].

Raim, E. (ed.) (2008). Überlebende von Kaufering. Biographische Skizzen jüdischer ehemaliger Häftlinge. Materialien zum KZ-Außenlagerkomplex Kaufering. Berlin: Metropol.

Rodenhäuser, L. (2012). Zwischen Affirmation und Reflexion: eine Studie zur Rezeption von Zeitzeugen in Geschichtsdokumentationen. München: LIT.

Rogge, J.-U. & Rogge, R. (2004). Hörklassiker für Kinder. Der Deutschunterricht, 56(4), 64–78.

Rosenthal, G. (1997). Der Holocaust im Leben von drei Generationen. Familien von Überlebenden der Holocaust und von Nazi-Tätern. Gießen: Psychosozial-Verlag.

Sabrow, M. (2012). Der Zeitzeuge als Wanderer zwischen den Welten. In M. Sabrow & N. Frei (eds.), Die Geburt des Zeitzeugen nach 1945 (13–32). Göttingen: Wallstein.

Schreiber, W. (2009). Zeitzeugengespräche führen und auswerten. In K. Arkossy & W. Schreiber (eds.), Zeitzeugengespräche führen und auswerten. Historische Kompetenzen schulen (21–28). Neuried: Ars una.

Sheftel, A. (2018). Talking and Not Talking about Violence. Challenges in Interviewing Survivors of Atrocity as Whole People. Oral History Review, 45(2), 278–293.

Shenker, N. (2015). Reframing Holocaust Testimony. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Snyder, T. (2015). Bloodlands. Europa zwischen Hitler und Stalin (aus dem Englischen von Martin Richter, 5. Aufl.). München: C.H. Beck.

Dr. Anja Ballis, Chair of German Language Studies, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität Munich, Germany.